Surveilling a Middle East of the Heart, “Midrash” or Commentary

The Cinema of Amos Gitai (for Yaqeen Hammad, 2014-2025)

The humanity of the rebel

In the penultimate chapter of Power and Innocence, Rollo May takes up the rarified thought example of Albert Camus (a man he greatly admired) on what he calls “The Humanity of the Rebel.” In his essay, The Rebel, Camus writes with customary profundity and grace:

“Whatever we may do, excess will always keep its place in the heart of man, in the place where solitude is found, We all carry within us our places of exile, our crimes and our ravages. But our task is not to unleash them on the world; it is to fight them in ourselves and in others. Rebellion, the secular will not to surrender . . . is still today at the basis of the struggle. Origin of form, the source of real life, it keeps us always erect in the savage formless movement of history.”

—Albert Camus, The Rebel

And, so, we are returned to themes of vigilance, atonement, and greater “jihad” once again. For May, strife and interior struggle were givens of existence put—like Camus—to astonishingly good use over time. He would often give a version of a talk on the “The Wounded Healer” when invited to speak in later years. In this lecture, May stressed the irrevocability of anxiety and turbulence if one aspired to become an effective psychotherapist. I recall a dialogue one evening as an awestruck student conveyed a sort of mock-authenticity through a somewhat forced show of slightly false modesty. How can I hope to help the client, seemed to be this young man’s point before his distinguished interlocutor, when I’m not feeling especially well-adjusted myself? “You say ‘well-adjusted,’” Rollo responded abruptly. “You don’t want to be well-adjusted. If you are well-adjusted, you’ll never be a good therapist. You won’t be a good anything.” He paused momentarily before delivering the coup de grâce: “Maybe you’ll make a good soldier.” Adjustment, after all, is a process of fitting oneself upon a Procrustean bed while excising very possibly the most human parts of oneself so as to get along more expediently with a Nietzschean herd.

In considering the interrelationship between the rebel’s humanity and a reimagined sense of community and planet-mindedness, May quotes Frank Barron, an atypically interesting American psychologist and philosopher, on matters of creativity:

“. . . Rebellion—resistance to acculturation, refusal to ‘adjust,’ adamant insistence on the importance of the self and of individuality —is very often the mark of the healthy character. If the rules deprive you of some part of yourself, then it is better to be unruly . . . The great givers to humanity often have proud refusal in their souls, and they are aroused to wrath at the shoddy, the meretricious, and the unjust, which society seems to produce in appalling volume.”

—Frank Barron, Creativity and Psychological Health: Origins of Personal Vitality and Creative Freedom

We may think of Patti Smith once again and, also, her powerful performance of Dylan’s Masters of War. An essential aspect of Dylan’s genius and character, it seems to me, is his courage in hitting upon all conceivable notes over the course of a spellbinding artistic journey. May often spoke about the importance of anger and could be quite direct in expressing it. He was in no way an angry man. Rather, he learned to integrate legitimate anger into a nuanced “many-hued reflection” (as Goethe puts it in Faust) and affective tapestry. It was something moving to behold and personally instructive as well.

Toward a new community

The concluding chapter of Power and Innocence is entitled “Toward a New Community.” Here May speaks wisely (we can forgive the slightly outdated language with respect to gender) in hopeful anticipation of a far, far saner world:

“Compassion is the name of that form of love which is based on our knowing and understanding each other. Compassion is the awareness that we are all in the same boat and that we all shall either sink or swim together. Compassion arises from the recognition of community. It realizes that all men and women are brothers and sisters, even though a disciplining of our own instincts is necessary for us even to begin to carry out that belief in our actions.”

—Rollo May, Power and Innocence

“Farewell to Innocence” is the opening section of this final chapter; “Toward a New Ethic” is the one with which it concludes. Pressing themes concerning morality and justice in which Melville’s novella, Billy Budd, is taken up by way of literary example. A poem by Martin Buber (someone Rollo also admired enormously), “Power and Love,” serves as the chapter’s frontispiece. Buber’s vision of a Holy Land was one in which all peoples, Arabs and Jews especially, would coexist in mutual cooperation and peace. Mahmoud Khalil, just released after three months of incarceration on utterly contrived charges (though his ordeal is, likely, far from over) has made this same point consistently and did so again immediately upon his release. It’s what Amos Gitai’s extraordinary filmography is all about as well: Beyond Boundaries.

Anyone who imagines that Benjamin Netanyahu or Donald Trump has anything remotely principled or beneficent in mind in their self-serving agendas and never-ending exploits is psychologically naive and a bit brainwashed by this point in time—tapped into predictable platforms and podcasts and exiled from inmost pathways and Blakean “doors of perception.” Lord knows, the ongoing proliferation and stockpiling of increasingly ungodly nuclear arms by military superpowers across the globe (along with our psychotically, indeed suicidally, neglected and abused Mother Earth) is a matter of escalating existential dread and denial, however unconscious this may be. As I state in my post in sympathy with Melville, our governments and constituent minds are typified by ludicrously too much fire and an alarming paucity of light.

It is likely significant that Dylan selects A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall for Patti Smith to perform on the occasion of his receipt of the Nobel Prize for Literature from out of a stunning body of work. In Chronicles: Volume One, Dylan writes that he was inspired to compose this haunting song to express the feeling he had upon reading through microfiche newspapers in the New York Public Library:

"After a while you become aware of nothing but a culture of feeling, of black days, of schism, evil for evil, the common destiny of the human being getting thrown off course. It’s all one long funeral song."

—Bob Dylan, Chronicles: Volume One

Gitai (who admirably chooses to forego war and theft for filmmaking and a camera), Krystina, and 11 year old Gaza “influencer” Yaqeen Hammad strike me as having the message quite right. Such beings reside on infinitely higher planes with respect to values, heart, and moral compass than those who wield and abuse power and many of the rest of us, too. We may think of Anne Frank as their patron saint. Anne, Krystina, and Yaqeen: a holy trinity of youthfully attentive and mindfully turned-on souls.

The God Mother

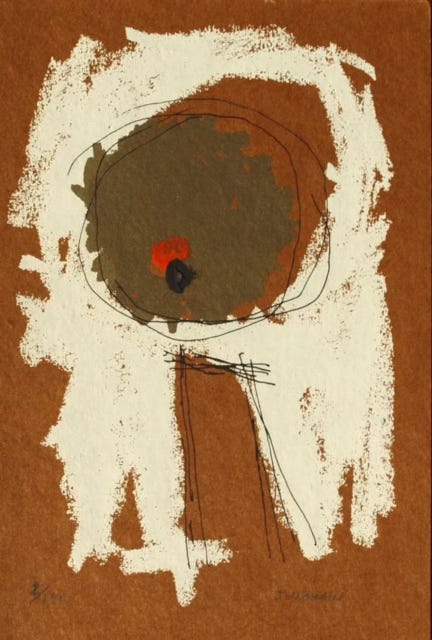

The God Mother is one of Krystina’s most haunting creations—a painting expressing some of the agony, wonder, and sheer horror of existence no less than a prayer for safe passage, patronage, and sanctuary. Sensitive viewers will observe the stigmata, passion, and inward politic—a fragmentation and shattering (known, more formally, as “dissociation”) reconciled briefly through imagination, color, and form.

Nietzsche suggests that we are all crucified in some way; it is, in fact, the human condition. Questions reflexively arise: What shall we do about it? How best to move through a world by which one has been so unjustly mistreated and visibly scarred? The oft-quoted last line of Nietzsche’s Ecce Homo (words proclaimed by Pilate when presenting Jesus to the crowd) makes our point plainly: “Have I been understood?—Dionysus versus the Crucified.” Nietzsche would have us embrace both existential responses in honoring the fuller range of experience with all its suffering, joy, sadness, camaraderie, frivolity, cruelty and love. He advocates playing out our hands with fervor while trying not to cause harm to others. The subtitle to Nietzsche’s final book is instructive: How One Becomes What One is. It’s a line taken from the Ancient Theban poet, Pindar. “Self-creation,” writes the philosopher in anticipation of Krystina’s parallel insight, “that rare and most difficult art.”

Musical Coda: Patti Smith’s Peaceable Kingdom

Peaceable Kingdom is a song written by Patti Smith and Tony Shanahan in memory of Rachel Corrie, a 23 year old American activist who was crushed to death in 2003 by an Israeli bulldozer while attempting to forestall the demolition of a Palestinian home in Gaza. The song was composed, Patti tells us, as a possible comfort for Corrie’s parents, who seem to have admirably devoted their lives to the principles of fairness and peace for which their daughter gave her life.

“This is a live recording from Electric Lady Studios. Thinking of the dying young all over the world. Young soldiers, young women fighting for their freedom, for their education, their voice. And also thinking of the mothers and fathers who bring them into the world, only to see them unjustly taken away.”

—Patti Smith

Patti Smith, "Peaceable Kingdom"

Surveilling a Middle East of the Heart

“Art flies around truth but with the definite intention of not getting burnt. Its capacity lies in finding in the dark void a place where the beam of light can be intensely caught, without this having been perceptible before.”—Franz Kafka, The Blue Octavo Notebooks